By Charly D. Miller, Paramedic, EMS Author & Educator, Consultant

Updated August, 2002

Emergency responders sometimes encounter excited, agitated and/or violent individuals.

To ensure patient* and provider* safety, to facilitate thorough evaluation and care, these individuals often require restraint. However, forcefully restraining a patient in the prone position is emphatically not appropriate! Besides seriously interfering with access for examination and care provision, the use of forceful-prone-restraint (with or without hobble or "hogtie" restraint) has been associated with causing patient death from "positional asphyxia."(1, 2, 3, 15, 17, 19, 21)

* For the purposes of this article, the term, "patient" also means "client," "student," "suspect," "criminal," "inmate," and the like. Correspondingly, the terms, "provider" or "responder" refer to law enforcement or correctional officers, fire or EMS or emergency department personnel, hospital or psychiatric facility personnel, employees of a residential facility or school for developmentally-disabled individuals, and the like.Alternative methods of restraint are available to every emergency responder; methods easily employed and equally as immobilizing as forceful-prone-restraint ... methods that allow full access to the patient ... without the threat of death from positional asphyxia.

Physical or mechanical restraint of an individual is always a "last resort." Less-restrictive means of "restraint" (such as verbal cues or de-escalation) should always be used before resorting to hands-on or mechanical restraint. When physical restraint IS required, only the "least restrictive" means of control may be used. (Only the minimum amount of restraint required to accomplish safety, and thorough evaluation/treatment.) Additionally, provider and patient safety must be ensured during initiation, accomplishment, and maintenance of physical restraint.

DEFINITIONS

Photo © 1997 Bioguardian Systems, Inc. |

is defined as placing an individual's body FACE-DOWN upon a surface (such as the ground or an ambulance wheeled stretcher), and physically applying pressure to his posterior shoulders, torso, hips, and/or upper legs – physically preventing him from moving out of the prone position). |

is defined as placing a patient FACE-DOWN upon an ambulance wheeled stretcher or long back board (or similar device), and then using restraint STRAPS to forcefully affix the patient's shoulders, torso, hips, and/or upper legs – mechanically preventing him from moving out of a prone position. |

Photo © 1997 Howard M. Paul |

Photo © 1997 Howard M. Paul |

|

individual's wrists together behind his back, binding his ankles together, then bending his knees and tying his bound wrists and ankles together above his back. This practice has also been called "hog-tying." Hobble restraint may or may not be performed while an individual is in a prone position.(1, 3, 9, 11, 19) |

Positional Asphyxia is most simply defined as when the position of a person's body interferes with respiration, resulting in death from asphyxia or suffocation. ANY body position that obstructs the airway, OR that interferes with the muscular or mechanical components of respiration, may result in positional asphyxia.(3, 4, 5, 7, 15)

In order to pronounce someone dead due to "POSITIONAL ASPHYXIA" (whether the positional asphyxia death is restraint-related, or not), requires ALL of the following three key elements:(4)

When specifically referring to Restraint-Related Positional Asphyxia deaths, the phrase "Restraint Asphyxia" was first proposed in 1993.(9, 15) This phrase has been readily adopted by individuals who are well educated in this subject. However, several other phrases are still used to describe incidents of Restraint Asphyxia: "Mechanical Asphyxiation," "Traumatic Asphyxiation," "Sudden In-Custody Death," and the like.

Why is this terminology-fuss "important?" Historically, the phrase, "Positional Asphyxia" implies "passive entrapment" of an individual, and is usually considered an "accidental" cause of death.(15) Restraint Asphyxia death is clearly the result of "elective" entrapment. Thus, Restraint Asphyxia is "homicide."

Why is this terminology-fuss "important?" Historically, the phrase, "Positional Asphyxia" implies "passive entrapment" of an individual, and is usually considered an "accidental" cause of death.(15) Restraint Asphyxia death is clearly the result of "elective" entrapment. Thus, Restraint Asphyxia is "homicide."

Prior to the early 1990's, hobble (hogtie) restraint was frequently employed by law enforcement officers for control of significantly combative parties. In response to restraint asphyxia death research, many law enforcement and correctional services across the country – and around the world – have since BANNED the use of hobble restraint.(6, 6a-6g) Unfortunately, even these "responsible" law enforcement services continue to be confused about the greater importance of avoiding forceful-prone-restraint!

Forensic pathologists began studying sudden deaths related to law enforcement use of restraint in the 1980's.(7) As restraint asphyxia research continues, more and more is understood. Unfortunately, controversy and confusion is sometimes generated by researchers.

A November of 1997 study published in the Annals of Emergency Medicine journal, by Chan, et al (emergency and "pulmonary" physicians) has been frequently – and erroneously – cited as having shown that "Police Hogtie Restraint Doesn't Kill."(10, 11, 12) Within their report (albeit only briefly, and in vague terms), Chan et al. admitted that their research did NOT study hobble restraint as it is performed in the field.(8, 21) [This study, related letters and reviews, is available in my Web Site's "RESTRAINT ASPHYXIA LIBRARY."]

A November of 1997 study published in the Annals of Emergency Medicine journal, by Chan, et al (emergency and "pulmonary" physicians) has been frequently – and erroneously – cited as having shown that "Police Hogtie Restraint Doesn't Kill."(10, 11, 12) Within their report (albeit only briefly, and in vague terms), Chan et al. admitted that their research did NOT study hobble restraint as it is performed in the field.(8, 21) [This study, related letters and reviews, is available in my Web Site's "RESTRAINT ASPHYXIA LIBRARY."]

In their most recently published study – September, 1998 (13) – Chan, et al conclude that "a combination of factors" results in restraint asphyxia, not hobble restraint alone. In that, they are correct. Unfortunately, they then suggest that the other factors involved are "more important" (more responsible for the restraint asphyxia) than the restraint factor. Their suggestion is wrong. The "other factors" – by themselves – would not result in death, either.(20, 21)

In their most recently published study – September, 1998 (13) – Chan, et al conclude that "a combination of factors" results in restraint asphyxia, not hobble restraint alone. In that, they are correct. Unfortunately, they then suggest that the other factors involved are "more important" (more responsible for the restraint asphyxia) than the restraint factor. Their suggestion is wrong. The "other factors" – by themselves – would not result in death, either.(20, 21)

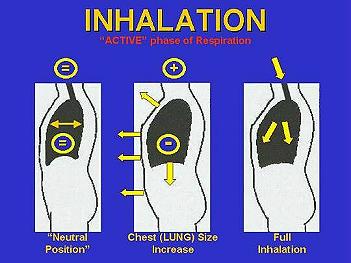

To fully understand the deadly relationship between restraint asphyxia and forceful-prone-restraint

(or prone-hobble-restraint), a basic understanding of respiratory physiology

(normal breathing function) is required.

Effective Respiration depends upon a combination of three critical elements:

If any part of the upper or lower airway becomes obstructed, respiration is impeded or completely prevented. If lung tissue or circulation is severely diseased, or damaged by injury, oxygen and carbon dioxide are not exchanged adequately and breathing is ineffective. Additionally, even with a completely open airway, perfectly healthy lungs and normal circulation, if a failure of the mechanical component of respiration occurs (the muscular pump or bellows system), effective respiration cannot be achieved.

An Effectively Functioning Muscular Pump or Bellows System

requires a combination of three critical elements:

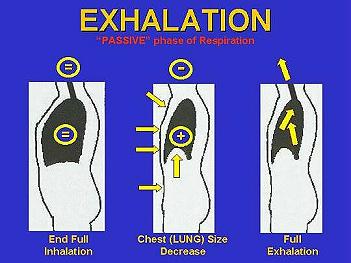

in a "neutral" position – a fixed, unchanging position – the air-pressure INSIDE the chest/lungs would be the SAME as the air-pressure OUTSIDE the body. An EQUAL air-pressure inside and outside of the body results in NO AIR MOVEMENT between these two spaces. NO "breathing." |

Graphic © 2001, C.D.Miller |

Graphic © 2001, C.D.Miller |

and energy-expenditure is required to make the intrathoracic (internal chest/lung) space LARGER, inspiration is also called the "Active Phase" of respiration. |

– and no "energy-expenditure" – is required to make the intrathoracic space smaller, expiration is also called the "Passive Phase" of respiration. |

Graphic © 2001, C.D.Miller |

Graphic © 2001, C.D.Miller |

cannot be changed, because the size of the intrathoracic space cannot be changed, NO AIR MOVEMENT occurs between the lungs and the external atmosphere. |

When breathing becomes difficult (for any reason), accessory muscles in the trunk, neck, and arms are automatically employed to assist the intercostal muscles and diaphragm in changing the internal size of the chest, and creating the intrathoracic air-pressure changes required to achieve inspiration and expiration.

But, when forcefully-prone-restrained, a person's muscular bellows system becomes significantly compromised. By forcefully compressing the shoulders and torso to a surface, chest expansion is seriously restricted or completely prevented. By forcefully compressing the person's diaphragm (lower back and/or hips) against a surface, diaphragmatic excursion and displacement of abdominal contents is seriously restricted or completely prevented. Thus, forceful-prone-restraint significantly restricts or prevents inhalation.(1, 3, 4, 9)

If placed in a forceful-prone-position and also hobble restrained, a person's muscular bellows system becomes even more significantly compromised. The person's diaphragm (the largest/strongest muscle of respiration) is compressed against a surface, preventing downward excursion and displacement of abdominal contents. And, when in hobble restraint, the individual's shoulders are pulled up and back, locking the chest wall into a hyperexpanded position – seriously limiting chest wall relaxation OR further chest wall expansion.(1) Therefore, BOTH inhalation and exhalation are significantly prevented when someone is placed in a prone-hobble-restrained position.

Although forceful-prone-restraint and/or forceful-prone-hobble-restraint restriction of accessory muscles has not been studied, it is obvious to unbiased researchers that "any restraint that prevents a change of position could restrict breathing further by preventing (accessory) muscles from assisting in respiration."(3)

When forcefully-prone-restrained or prone-hobble-restrained, an individual must lift his entire body off of the surface he is placed upon – against physical pressure and/or restraint devices – using only his abdominal muscles, simply to take in or let out a little bit of breath. The muscular act of breathing requires a greatly increased physical effort – a greatly increased energy-expenditure. Yet, this great effort/energy-expenditure achieves (at best) only the tiniest volume of breath.

In addition to the respiratory compromise caused by forceful-prone-restraint or prone-hobble-restraint, both these restraint positions significantly interfere with care providers being able to accomplish a complete and thorough patient examination, and significantly interfere with responders' performance of required emergency care procedures! If a patient is forcefully-prone-restrained or prone-hobble-restrained, care providers are restricted from accessing, evaluating, or controlling the most vital parts of the individual's body.

As supported by all restraint research (including that of Chan et al), interference with respiratory bellows system function is only One Factor that links use of forceful-prone-restraint or prone-hobble-restraint to restraint asphyxia death. Other, (equally important) factors include the patient's behavior and activities that precede and correspond with the use of forceful-prone-restraint or prone-hobble-restraint.

People who legitimately require total-body-restraint consistently experience Two to Three Phases of Extreme Muscle Exertion and Energy Expenditure prior to dying from restraint asphyxia.

(or "agitated delirium").(9) |

Photo © 1997 Howard M. Paul |

Regardless of its cause, the excited delirium of Phase 1 results in profound physical exertion,

Regardless of its cause, the excited delirium of Phase 1 results in profound physical exertion, The time-length of Phase 1 varies with each incident, each incident's cause, and has variable effects upon each individual. Persons with excited post-seizure or low blood sugar episodes, or persons with acute head injuries, can experience total body exhaustion in just a few minutes. Persons with chronic diseases can become exhausted much faster than otherwise "healthy" individuals, when experiencing excited delirium.(11, 14, 16)

The time-length of Phase 1 varies with each incident, each incident's cause, and has variable effects upon each individual. Persons with excited post-seizure or low blood sugar episodes, or persons with acute head injuries, can experience total body exhaustion in just a few minutes. Persons with chronic diseases can become exhausted much faster than otherwise "healthy" individuals, when experiencing excited delirium.(11, 14, 16) Regardless of its time-length, Phase 1 continues until the individual's "out of control" behavior is finally noticed by someone, and/or becomes so threatening to someone, that law enforcement, EMS, and/or fire department personnel are summoned.

Regardless of its time-length, Phase 1 continues until the individual's "out of control" behavior is finally noticed by someone, and/or becomes so threatening to someone, that law enforcement, EMS, and/or fire department personnel are summoned.

Photo © 1997 Howard M. Paul |

Next, the individual is usually placed in wrist restraints, with or without ankle restraints, and may be released from the forceful-prone-position. If release from forceful-prone-restraint occurs before the individual expires – and the individual is not impeded from moving to his side – this can be considered a "medium-restrained" individual. Once medium restraint has been accomplished, Phase 2 ends.

Next, the individual is usually placed in wrist restraints, with or without ankle restraints, and may be released from the forceful-prone-position. If release from forceful-prone-restraint occurs before the individual expires – and the individual is not impeded from moving to his side – this can be considered a "medium-restrained" individual. Once medium restraint has been accomplished, Phase 2 ends.

Photo © 1997 Howard M. Paul |

Application of total-body-restraint begins Phase 3.

Application of total-body-restraint begins Phase 3.

If placed in forceful-prone-restraint during Phase 3, the energy required to fuel the individual's muscular ability to breathe is entirely ABSENT. The forcefully-prone-restrained individual becomes lethally exhausted within seconds.(1, 2, 3, 5, 8)

The individual enters respiratory arrest, closely-followed by cardiac arrest.

The individual enters respiratory arrest, closely-followed by cardiac arrest.

Pathophysiology of The Restraint-Asphyxia Exertional Phases

("WHY are these Phases so Lethal?!"):

Extreme physical energy expenditure generates excessive production of adrenalin and noradrenalin ("catecholamines"). A progressively-increasing amount of these body-chemicals in the individual's system occurs – creating a "hypercatabolic state." A hypercatabolic state weakens ALL the body's muscles – especially the respiratory muscles.(3, 9) |

Graphic © 1997 C.D.Miller |

Reay et al report, "Energy that is expended by the contractile machinery of the body is subtracted from the respiratory muscle needs. Muscle fatigue may induce the central nervous system to shunt energy to contracting muscles. A deficit in energy supply to respiratory muscles can influence their performance. A decrease in chemical energy supply to respiratory muscles will hasten their failure as well as the failure of other muscle groups."(3)

Reay et al report, "Energy that is expended by the contractile machinery of the body is subtracted from the respiratory muscle needs. Muscle fatigue may induce the central nervous system to shunt energy to contracting muscles. A deficit in energy supply to respiratory muscles can influence their performance. A decrease in chemical energy supply to respiratory muscles will hasten their failure as well as the failure of other muscle groups."(3) O'Halloran and Lewman conclude, "First, the psychiatric or drug-induced state of agitated delirium coupled with police confrontation undoubtedly places catecholamine stress on the heart. Second, the hyperactivity associated with agitated delirium coupled with struggling with police and against restraints undoubtedly increases the oxygen delivery demands of the heart and lungs. Finally, the hogtied position clearly impairs breathing in situations of high oxygen demand by inhibiting chest wall and diaphragmatic movement."(9)

O'Halloran and Lewman conclude, "First, the psychiatric or drug-induced state of agitated delirium coupled with police confrontation undoubtedly places catecholamine stress on the heart. Second, the hyperactivity associated with agitated delirium coupled with struggling with police and against restraints undoubtedly increases the oxygen delivery demands of the heart and lungs. Finally, the hogtied position clearly impairs breathing in situations of high oxygen demand by inhibiting chest wall and diaphragmatic movement."(9)

Research also suggests that the violent muscular activity that occurs during each Phase causes an excessive "lactic acid" production, producing "a profound metabolic acidosis ... associated with cardiovascular collapse following exertion in a restrained position."(16) Metabolic acidosis is a state of body-chemical imbalance, that – by itself – can kill someone. "Stimulant drugs such as cocaine may promote further metabolic acidosis and impair normal behavior regulatory responses. Restrictive positioning of combative patients may impede appropriate respiratory compensation for this acidemia."

More study is needed regarding the acidosis theory. But, it is entirely likely that "Good outcomes are still possible despite the pronounced level of" metabolic acidosis, if the individual is treated with "aggressive hyperventilation" and/or rapid adminsitration of IV "bicarbonate therapy."(16)

More study is needed regarding the acidosis theory. But, it is entirely likely that "Good outcomes are still possible despite the pronounced level of" metabolic acidosis, if the individual is treated with "aggressive hyperventilation" and/or rapid adminsitration of IV "bicarbonate therapy."(16)

OVERWEIGHT INDIVIDUALS – those with "a large abdominal panniculus" (that's a medically-polite phrase meaning, "a big, fat, belly") – clearly appear to be at even greater risk for rapid onset of restraint asphyxia.(11, 14, 21) Dr. Reay reports, "A large, bulbous abdomen (a beer belly) presents significant risks because it forces the contents of the abdomen upward within the abdominal cavity when the body is in a prone position. This puts pressure on the diaphragm, a critical muscle responsible for respiration, and restricts its movement. If the diaphragm cannot move properly, the person cannot breathe."(14)

Think about it. If someone is overweight, forcefully restraining them on their stomach will not only prevent the contents of their belly from having room to move out of the way of their descending diaphragm, it will squish their belly contents UP INTO their diaphragm and lungs ... diminishing the size of their lung expansion ... entirely preventing their diaphragm from having room to move down into their belly ... and entirely preventing them from being able to change the internal size of their chest.

Think about it. If someone is overweight, forcefully restraining them on their stomach will not only prevent the contents of their belly from having room to move out of the way of their descending diaphragm, it will squish their belly contents UP INTO their diaphragm and lungs ... diminishing the size of their lung expansion ... entirely preventing their diaphragm from having room to move down into their belly ... and entirely preventing them from being able to change the internal size of their chest.

Those who persist in ignoring this danger often cite the argument, "We only use prone/hobble restraints for a short period of transport time." Unfortunately for these providers and their patients, short transport times do not prevent restraint asphyxia death!

Published studies of deaths attributed to restraint asphyxia do not consistently (nor accurately) document the time-lapse between placement in forceful-prone-restraint and onset of unconsciousness or death. However, of the cases that HAVE reported this time period(1, 2, 3, 8), the average time between restraint application and onset of death was only 5.6 minutes!

Published studies of deaths attributed to restraint asphyxia do not consistently (nor accurately) document the time-lapse between placement in forceful-prone-restraint and onset of unconsciousness or death. However, of the cases that HAVE reported this time period(1, 2, 3, 8), the average time between restraint application and onset of death was only 5.6 minutes!

A Wisconsin EMS case of restraint asphyxia death (one of several, but the only one to be published) occurred when the patient was "only" restrained prone and in hand cuffs (not hobbled), and was attended by a paramedic "for a five mile ambulance trip to the hospital." The patient died after being loaded into the ambulance, but prior to arrival at the hospital. The patient was not successfully resuscitated.(2)

A Wisconsin EMS case of restraint asphyxia death (one of several, but the only one to be published) occurred when the patient was "only" restrained prone and in hand cuffs (not hobbled), and was attended by a paramedic "for a five mile ambulance trip to the hospital." The patient died after being loaded into the ambulance, but prior to arrival at the hospital. The patient was not successfully resuscitated.(2)

Stratton et al reported two cases of hobble-restraint-induced asphyxia death occurring while the patient was in the care of a paramedic.(1) In each of Stratton's cases, a paramedic witnessed the patient's respiratory and/or cardiopulmonary arrest, immediately released the patient from restraints, and initiated advanced life support. In each case, all prehospital and inhospital emergency medical resuscitation efforts failed.

Stratton et al reported two cases of hobble-restraint-induced asphyxia death occurring while the patient was in the care of a paramedic.(1) In each of Stratton's cases, a paramedic witnessed the patient's respiratory and/or cardiopulmonary arrest, immediately released the patient from restraints, and initiated advanced life support. In each case, all prehospital and inhospital emergency medical resuscitation efforts failed.

Thus, "We only use them for a short period of transport time" is not a legitimate excuse to continue using forceful-prone or prone-hobble restraint.

Thus, "We only use them for a short period of transport time" is not a legitimate excuse to continue using forceful-prone or prone-hobble restraint.

Additionally, according to ALL published case studies, deaths from restraint asphyxia do not respond to prehospital OR inhospital emergency resuscitation efforts.

[(To read the case study of an individual who entered restraint-related respiratory arrest, but who was successfully resuscitated prior to full cardiopulmonary arrest, read my "Restraint-Related Near-Death" Case Study, posted on my web site's "Restraint Asphyxia Newz" page.)]

[(To read the case study of an individual who entered restraint-related respiratory arrest, but who was successfully resuscitated prior to full cardiopulmonary arrest, read my "Restraint-Related Near-Death" Case Study, posted on my web site's "Restraint Asphyxia Newz" page.)]

Clearly, the use of forceful-prone-restraint or prone-hobble-restraint poses an unacceptable risk of death from restraint asphyxia. Clearly, the use of any form of PRONE restraint interferes with care providers' access to the patient for accomplishing a complete and thorough examination – interferes with performance of ALL required emergency care procedures. Clearly, the use of forceful-prone-restraint violates the emergency medicine Prime Directive, to "Do No Harm!"

Thus, such practices must immediately be banned

from ALL emergency responders' protocols of operation.

When dramatically changing any previously-accepted operational technique from use – when implementing a "change" in providers' long-time behaviors or practices – it is IMPERATIVE that providers be EDUCATED as to WHY the change must occur. [Parts 1 and 2 of this article!] Then, it is IMPERATIVE to simultaneously implement an equally-effective alternative to the banned / changed technique.

What follows is an in-depth description of the steps required to safely transfer a forcefully-prone-restrained or prone-hobble-restrained individual to a supine position; and the steps for application of a total-body-restraint technique that is actually even MORE immobilizing than the use of forceful-prone-restraint or prone-hobble-restraint. This technique of total-body-restraint accomplishes the needs of MEDICAL restraint (allowing care providers full access to the patient for performing a complete examination, and affording unimpeded performance of all emergency care procedure required)

What follows is an in-depth description of the steps required to safely transfer a forcefully-prone-restrained or prone-hobble-restrained individual to a supine position; and the steps for application of a total-body-restraint technique that is actually even MORE immobilizing than the use of forceful-prone-restraint or prone-hobble-restraint. This technique of total-body-restraint accomplishes the needs of MEDICAL restraint (allowing care providers full access to the patient for performing a complete examination, and affording unimpeded performance of all emergency care procedure required)

– yet does not threaten the patient's life (or the providers' livelihood)!

SUPINE TOTAL-BODY-RESTRAINT

|

Photo © 1997 Howard M. Paul |

Photo © 1997 Howard M. Paul |

and in hobble restraints, remove the hobble (the tie that binds the wrists to the ankles) and the handcuffs, and assess for respiratory or cardiopulmonary arrest.

If Rescue Breathing is indicated, implement it (!) |

[The following steps outline the manner that the patient should be supinely restrained to a long back board. However, from here on, we will assume that the restrained patient was NOT unconscious upon your arrival.](2B) If the side-positioned, restrained patient is CONSCIOUS (still combative, OR NOT),

(3) Keep the restrained, conscious, patient on his side until a "sufficient number of people" are available to control the patient during alternative restraint replacement.

At least FIVE PEOPLE are required to accomplish the safe transfer of significantly violent individuals from law enforcement restraint to MEDICAL restraint: one person to control each limb/major joint, and one person to apply alternative restraints.

At least FIVE PEOPLE are required to accomplish the safe transfer of significantly violent individuals from law enforcement restraint to MEDICAL restraint: one person to control each limb/major joint, and one person to apply alternative restraints.

Additionally, someone needs to be identified as the "Team Leader." The Team Leader is the person "calling the shots," and should be the person who knows how to safely accomplish the restraint transfer! ("Team Leader" assignment should NEVER be based upon "rank!")

Additionally, someone needs to be identified as the "Team Leader." The Team Leader is the person "calling the shots," and should be the person who knows how to safely accomplish the restraint transfer! ("Team Leader" assignment should NEVER be based upon "rank!")

All assisting persons need to know what their "assigned limbs" are – and what the "plan" is – before any action is actually implemented.

All assisting persons need to know what their "assigned limbs" are – and what the "plan" is – before any action is actually implemented.

(4A) Bring a LONG BACK BOARD to the Side of the Patient!

This is important for several reasons.

This is important for several reasons.

FIRST: Most individuals requiring total-body-restraint have an altered level of consciousness, AND have incurred SOME kind of trauma during one or more of the exertional Phases preceding application of total-body-restraint. (If not during Phase 1, then during all the chase-&-tackle stuff of Phase 2!) Thus, ALL individuals requiring total-body-restraint

FIRST: Most individuals requiring total-body-restraint have an altered level of consciousness, AND have incurred SOME kind of trauma during one or more of the exertional Phases preceding application of total-body-restraint. (If not during Phase 1, then during all the chase-&-tackle stuff of Phase 2!) Thus, ALL individuals requiring total-body-restraint

SHOULD be SPINALLY IMMOBILIZED!

SECOND: Use of a long back board will afford immediate and continuous SUPINE total-body-restraint, in addition to making it much SAFER to TRANSFER the patient to the NEXT LEVEL of CARE PROVIDER!

SECOND: Use of a long back board will afford immediate and continuous SUPINE total-body-restraint, in addition to making it much SAFER to TRANSFER the patient to the NEXT LEVEL of CARE PROVIDER!

If the first-responding care providers are not the transporting care providers, having the patient supinely-restrained to a long back board (LBB) means that the patient can remain restrained to the LBB – can be lifted to the transporting care providers' wheeled stretcher without having to alter (untie!) ANY of the restraints!

If the first-responding care providers are not the transporting care providers, having the patient supinely-restrained to a long back board (LBB) means that the patient can remain restrained to the LBB – can be lifted to the transporting care providers' wheeled stretcher without having to alter (untie!) ANY of the restraints!

When the next level of care provider is the emergency department staff, having the patient supinely-restrained to a LBB means that the patient can remain restrained to the LBB – can be lifted to the ED bed without having to alter (untie!) ANY of the restraints!

When the next level of care provider is the emergency department staff, having the patient supinely-restrained to a LBB means that the patient can remain restrained to the LBB – can be lifted to the ED bed without having to alter (untie!) ANY of the restraints!

[Concern about pressure sores caused by extended periods of time restrained to a LBB, or LBB-related patient discomfort increasing agitation(22) is entirely negated by the fact that: Once in the ED, the patient can be chemically sedated (discontinuing agitation), and (if cleared by X-ray) can be removed from the LBB prior to pressure sores becoming an issue!]

[Concern about pressure sores caused by extended periods of time restrained to a LBB, or LBB-related patient discomfort increasing agitation(22) is entirely negated by the fact that: Once in the ED, the patient can be chemically sedated (discontinuing agitation), and (if cleared by X-ray) can be removed from the LBB prior to pressure sores becoming an issue!]

(4B) Put the law-enforcement-restrained patient on the Long Back Board, ON HIS SIDE, and prepare to transfer him to LBB restraint.

Position all responders around the patient and LBB to ensure optimal control of the individual when law enforcement restraints are gradually removed.

Position all responders around the patient and LBB to ensure optimal control of the individual when law enforcement restraints are gradually removed.

Remove all "posterior" restraint (handcuffs and/or hobble ties), while maintaining physical control of the patient's wrists/arms, shoulders/hips, and place the patient SUPINE on the LBB.

Remove all "posterior" restraint (handcuffs and/or hobble ties), while maintaining physical control of the patient's wrists/arms, shoulders/hips, and place the patient SUPINE on the LBB.

Once SUPINE, the persons in charge of controlling each ARM should also place controlling-weight upon that arm's anterior SHOULDER – but, without placing weight upon the individual's chest.

Once SUPINE, the persons in charge of controlling each ARM should also place controlling-weight upon that arm's anterior SHOULDER – but, without placing weight upon the individual's chest.

Once SUPINE, the persons in charge of controlling each LEG should be placing controlling-weight upon the HIP and thigh of their assigned leg – NOT fussing with the individuals knees or ankles!

Once SUPINE, the persons in charge of controlling each LEG should be placing controlling-weight upon the HIP and thigh of their assigned leg – NOT fussing with the individuals knees or ankles!

[If you control the hip and thigh of a supinely-restrained individual, the corresponding knee and ankle can't "go" anywhere, or "do" anything! Fussing with knees and/or ankles only leads to "strength contests" between the patient and the restrainers – strength contests that will certainly aggravate the restrainers ... strength contests that the restrainers will likely "loose!"]

[If you control the hip and thigh of a supinely-restrained individual, the corresponding knee and ankle can't "go" anywhere, or "do" anything! Fussing with knees and/or ankles only leads to "strength contests" between the patient and the restrainers – strength contests that will certainly aggravate the restrainers ... strength contests that the restrainers will likely "loose!"]

(5) Restrain the Supine Pt's Chest to the LBB with a Restraint Strap:

Persons in charge of controlling each arm should extend ONE arm/wrist UP (above the patient's head), and ONE arm/wrist DOWN (by the patient's thigh). This "split" arm placement technique physiologically interferes with the patient's ability to use his strong abdominal muscles to assist his struggles against restraint. Additionally, this arm positioning technique most effectively holds the patient's chest in place for Chest Restraint placement.

About "Restraint Straps": I prefer using double-folded lengths of STRONG, roller gauze (SIX-ply Kerlix® or Kling®) for ALL restraint straps. When doubled and appropriately anchored, SIX-ply roller gauze is strong enough to hold even PCP-OD's! No "decontamination" is required of such restraints (they are disposable). And, if the patient seizes (requiring rapid removal of ALL restraint) ... out come the trauma shears!

About "Restraint Straps": I prefer using double-folded lengths of STRONG, roller gauze (SIX-ply Kerlix® or Kling®) for ALL restraint straps. When doubled and appropriately anchored, SIX-ply roller gauze is strong enough to hold even PCP-OD's! No "decontamination" is required of such restraints (they are disposable). And, if the patient seizes (requiring rapid removal of ALL restraint) ... out come the trauma shears!

To avoid chest-expansion-interference – yet still be an EFFECTIVE restraint – a Chest Restraint strap must be bilaterally-anchored to the LBB just above the axillary (armpit) area on either side of the patient.

To avoid chest-expansion-interference – yet still be an EFFECTIVE restraint – a Chest Restraint strap must be bilaterally-anchored to the LBB just above the axillary (armpit) area on either side of the patient.

Photo © 1997 Howard M. Paul |

Restraint Straps placed OVER one or both of the arms are BAD restraints. If that is done, the patient will be able to "squirm" one or both of his shoulders down and under the restraint strap. Such chest strap positioning is entirely ineffective, and a terrific waste of time and effort.

Restraint Straps placed OVER one or both of the arms are BAD restraints. If that is done, the patient will be able to "squirm" one or both of his shoulders down and under the restraint strap. Such chest strap positioning is entirely ineffective, and a terrific waste of time and effort.  LOOSE or Low-Anchored Chest Restraints tend to slide DOWN onto the chest, as the patient continues to struggle. As they begin to slide around, such inappropriately placed/anchored straps inevitably get snugged -up in a LOWER-chest position (ACROSS the chest), and can become a serious impedance to chest expansion.

LOOSE or Low-Anchored Chest Restraints tend to slide DOWN onto the chest, as the patient continues to struggle. As they begin to slide around, such inappropriately placed/anchored straps inevitably get snugged -up in a LOWER-chest position (ACROSS the chest), and can become a serious impedance to chest expansion.NEVER Engage an "Abdominal" Restraint! Even after the LBB-supinely-restrained individual is placed on an ambulance wheeled stretcher, do NOT employ an ABDOMINAL belt to keep the total-body-restrained individual on the stretcher. To do so, is to risk serious breathing interference.

(6) Restrain the Supine individual's Lower BODY to the LBB:

Photo © 1997 Howard M. Paul |

the patient can easily flex and rotate one or more of his legs, and escape the Lower Body restraint. Plz don't do that! |

This Lower Body restraint anchoring and placement technique will entirely defeat ALL attempts on the part of ALMOST ALL patients to "free" their legs from restraint. Most patients need no more than this Lower Body Restraint strap to keep them from injuring themselves or others.

(7) SECURE the Patient's ARMS to the LBB: Tie the center of a double-folded length of STRONG, roller gauze (SIX-ply Kerlix® or Kling®), around EACH of the patient's wrists. Double-knot it at the BACK of the wrist, so that a "FULL KNOT" is accomplished. This keeps the restraint "cuff" from becoming tighter, or looser, around the patient's wrist.

By knotting the "cuff" at the BACK of the patient's wrist, once anchored to the LBB, the anterior AC (inner elbow) surface ends up being better available for B/P measurement and IV procedures!

By knotting the "cuff" at the BACK of the patient's wrist, once anchored to the LBB, the anterior AC (inner elbow) surface ends up being better available for B/P measurement and IV procedures!

Photo © 1994 Michal Heron |

Tie the patient's left (non-dominant) wrist to an anchor point DOWNWARD, at the side of the Long Back Board – an anchor point that is JUST BEYOND his wrist, when his arm is FULLY extended. Then, pull the restraint-tails VERY TIGHT, "tractioning" the patient's arm STRAIGHT. If any "play" exists between the downward-placed wrist and the anchor point, pull the restraint-tails OUT of that anchor, and INTO to the next-distant point. Once the best distant anchor point is located, pull the restraint-tails VERY TIGHT, "tractioning" the patient's arm STRAIGHT. Then, snugly tie the restraint to that anchor point with a FULL KNOT.

Tie the patient's left (non-dominant) wrist to an anchor point DOWNWARD, at the side of the Long Back Board – an anchor point that is JUST BEYOND his wrist, when his arm is FULLY extended. Then, pull the restraint-tails VERY TIGHT, "tractioning" the patient's arm STRAIGHT. If any "play" exists between the downward-placed wrist and the anchor point, pull the restraint-tails OUT of that anchor, and INTO to the next-distant point. Once the best distant anchor point is located, pull the restraint-tails VERY TIGHT, "tractioning" the patient's arm STRAIGHT. Then, snugly tie the restraint to that anchor point with a FULL KNOT.[The "dominant-" vs. "non-dominant-" limb placement factor is not "VITAL!" Obviously, you probably won't know when the patient is Left-Handed. The above directives simply describe the "preferred" (and most effective) means of selecting which wrist to restrain UP, and which to restrain DOWN – especially considering the most usual position of the care provider (at the supine patient's LEFT SIDE) when enroute to the ED. The only, truly, important factor is that ONE wrist is restrained UP, and ONE wrist is restrained DOWN.]

REMEMBER: by restraining ONE arm above the patient's head and the OTHER at his side, you effectively disable the patient's ability to use his strong abdominal muscles to assist in attempts to defeat restraint.

And, by accurately ANCHORING restraints, you effectively disable the patient's ability to move his wrists up-&-down, or side-to-side. Thus, he is entirely, "medically," immobilized – he cannot interfere with complete assessment, blood pressure measurement, IV access, treatment provision, etc...

(8) Evaluate the Need for Ankle Restraints:

Often, the combination of appropriately placed and anchored chest-restraint-strap and lower-body-restraint-strap (and bilateral wrist-restraints) is sufficient to provide Total-Body-Restraint. However, if the patient is "DIVINELY INSPIRED" to defeat or escape from restraint (continues to extremely struggle against the Lower Body restraint), EMPLOY ANKLE RESTRAINTS.

Photo © 1997 Howard M. Paul |

Photo © 1994 Michal Heron |

Supine Position, and in a manner that is even more immobilizing than forceful-prone-restraint or prone-hobble-restraint.

Yet, he is also restrained in a manner that allows for |

Law Enforcement Options:

Unfortunately, law enforcement officers usually do not have a LBB to attach seriously-combative patients to.

Unfortunately, law enforcement officers usually do not have a LBB to attach seriously-combative patients to.

No matter what total-body-restraint methods are used by law enforcement officers, it is VITAL that they be educated about the causes of Restraint Asphyxia. Additionally, it must be emphatically stressed that suspects cannot remain restrained – in any way – on their stomachs, for ANY length of time!

No matter what total-body-restraint methods are used by law enforcement officers, it is VITAL that they be educated about the causes of Restraint Asphyxia. Additionally, it must be emphatically stressed that suspects cannot remain restrained – in any way – on their stomachs, for ANY length of time!

(1) If they are on their stomach, get them OFF IT! IMMEDIATELY!

(2A) Assess for level of consciousness and respiratory or cardiac arrest.

Get them OUT of everything if they are unconscious.

Get them OUT of everything if they are unconscious.

Then, while you provide resuscitation, restrain them supinely to a LBB.

Then, while you provide resuscitation, restrain them supinely to a LBB.

(2B) If they are conscious, leave them in the restraints – but KEEP them on their SIDE –

until you and your TEAM are ready to transfer them to Supine LBB Restraint.

until you and your TEAM are ready to transfer them to Supine LBB Restraint.

(3) Gather your TEAM of 5, identify the Team Leader, and discuss your PLAN for restraint transfer.

(4) Get them on a LBB, on their side, and position everyone for maximum control during restraint

transfer. Remove all posterior restraints, and physically restrain them SUPINE on the LBB.

transfer. Remove all posterior restraints, and physically restrain them SUPINE on the LBB.

(5) Secure the Chest Restraint Strap.

(6) Secure the Lower Body Restraint Strap.

(7) Secure one arm UP, and one arm DOWN.

(8) Consider the need for Ankle Restraint; tying the ankles TOGETHER first, if ankle restraint is needed.

Use of forceful-prone-restraint or prone-hobble-restraint has clearly been shown to contribute to rapid (irretrievable) death from restraint asphyxia. Medical care providers have no reason, excuse, or support for continuing to use such restraint techniques.

Appropriately anchored and engaged restraint straps can effectively restrain a SUPINE individual to a long back board, without compromising the individual's ability to breathe.

This alternative system of supine total-body-restraint provides restraint that is even MORE "immobilizing" than forceful-prone-restraint or hobble restraint – yet, allows medical care providers full access for patient examination, evaluation, and unimpeded provision of required medical care procedures.

Lastly, supine total-body-restraint prevents patient death from restraint asphyxia (and prevents provider-litigation for "wrongful death")!

The REFERENCE List for ALL parts of RESTRAINT ASPHYXIA – SILENT KILLER is available at http://www.charlydmiller.com/RA/restrasphyxref.html

Many of these reference articles are posted in Charly's RESTRAINT ASPHYXIA LIBRARY! If you want to read them, go to: http://www.charlydmiller.com/RA/RAlibrary.html

About the Author: Charly is an internationally-known emergency care author, EMS Instructor, Consultant, and Restraint Asphyxia Expert Witness. A paramedic since 1985 (nine years as a "Denver General" Paramedic), Charly is a seasoned prehospital emergency care provider. With her additional experience as a psychiatric medical technician and an Army National Guard helicopter medic, Charly is one of the country's most exciting and entertaining EMS educators.