Restraint |

|

|

W. Ann Maggiore, JD, NREMT-P & Robert B. Palmer, PhD, NREMT-P Published in the Journal of Emergency Medical Services March 2002, Vol. 27 No. 3, pages 84-104 |

Plz Note: My original Restraint Asphyxia Library posting of this article consisted of scanned PAGES from my copy of JEMS. Due to "layout" issues, the photography was published in a somewhat jumbled manner – poorly relating to the surrounding text. But, I left it alone.

Now that JEMS On-Line provides past issue articles in an archive that can be accessed by subscribers, this version of the "Exercise Restraint" article is derived from that archive. (Thus, it's much easier to read and print.)

But, whomever coded this article for On-Line posting got the photography even more screwed up than it originally was (in addition to completely missing an entire section of text). AND, the photos have never been identified by a "Figure" designation.

Because my review of this article heavily addresses it's photography, when posting this On-Line version, I rearranged the photography, and assigned each photo a "Figure" number.

NO "content" changes have been made by me.

[Figure 1 Photo © Craig Jackson] |

|

Medical & Legal Issues |

You've been there: you can hear your patient before you see them. They're sometimes engaged with police; other times you've been called by a family member. Often, your patient is under the influence of alcohol or drugs, making your assessment more difficult. Sometimes your patient has physical injuries, and you try to determine which came first: the injury or the aggressive behavior. Either way, your patient is a volcano ready to erupt. Your job: to safely treat and transport this patient to the hospital for evaluation.

You must consider some important things in this situation. First, consider your safety. You know the back of an ambulance is a very small place to be with a patient who can hurt you. Second, you must consider the patient's safety. You've heard the horror stories about "positional asphyxia" in ambulances and police vehicles. Then there's the potential legal liability. You've heard about EMS providers getting sued for improper patient handling. You have limited legal authority to force patients to seek further medical attention. So the key word is safety.

|

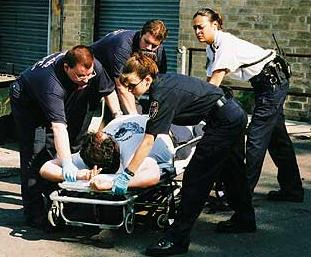

It's sometimes necessary to enlist help from the police or fire department when restraining a combative patient. [Figure 2 Photo © Craig Jackson] |

EMS providers must learn to assess threats and restrain patients in a manner that prevents injury to them as well as to us. This article explores the reasons patients become violent and the kinds of physical and chemical restraints appropriate for EMS use. It also delves into how to handle violent situations without exposing yourself to unreasonable legal liability.

SCOPE OF THE PROBLEM

How frequently do EMS providers encounter violent patients? According to current studies, fairly often. Researchers at the University of Kentucky School of Medicine conducted a one-month study of violent patients who required involuntary treatment and restraint.(1) They found EMS delivered 46% of these patients to the emergency department (ED); law enforcement transported 24%; family brought in 21.7%; and 9% came in on their own. Thus, more violent patients arrive at the ED by EMS transport than by any other means.

A 1998 study conducted at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, Tenn., indicates that violent situations occur in 5% of all EMS calls, with an additional 14% of calls precipitated by violence.(2) This study also found EMS documentation under-reports exposure to violence.

A third study conducted by Loma Linda (Calif.) University Medical Center found that EMS providers encounter a substantial amount of violence and injury due to on-the-job assaults.(3) Another Loma Linda University Medical Center study surveyed prehospital provider experiences with violence: 61% recounted assault on the job, with 25% reporting injury from the assault. Of those injured, 37% required medical attention.(4)

WHY DO PATIENTS BECOME VIOLENT?

It's instructive to examine the reasons patients become violent. Aggressive behavior can result from a number of medical and psychiatric conditions. Knowing the underlying cause of violent behavior can help us treat our patients during transport and increase the possibility of a safe trip to the ED for everyone involved.

The first Loma Linda study identified a number of factors that appear to play a role in violence against EMS personnel. Violence is more likely to occur:

Although substance abuse doesn't cause violence, it lowers a patient's threshold for controlling aggressiveness. Pour on the alcohol, and an otherwise docile person may become impossible to handle.

Other conditions that may cause violent behavior: Brain injuries, particularly frontal brain injuries, may cause patients to become violent. Hypoxia, which can result from injury or illness, can cause mood changes leading to violent behavior. Hypoglycemia may cause combativeness in patients. A confused or claustrophobic patient may become violent when they realize you're securing them flat on a board they don't want to be on. Epileptic seizures may cause a patient to behave uncontrollably. Finally, some patients become violent in response to pain or fear.

RESTRAINTS: DARNED IF YOU DO, DARNED IF YOU DON'T

No hard-and-fast rules govern patient restraints. On the one hand, EMS and law enforcement agencies have been sued for restraining patients improperly. Most such suits allege the restraints were a form of excessive force, ultimately causing the patient's death by positional asphyxia. On the other hand, one suit alleged a patient was not restrained securely enough. Examples of circumstances that led to lawsuits include:

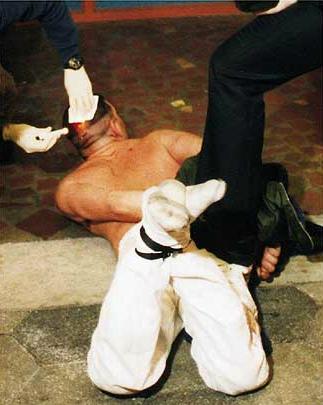

A Houston court awarded $800,000 to the family of a man who died after being hogtied (restrained with the ankles tied to the handcuffs behind the back, see [Figure 5] photo p. 92) during a confrontation with police and store security. A medical examiner ruled the man died of asphyxiation, caused by the hogtying and the officer's weight on him, and fluid in his lungs.

On July 30, 1999, a 51-year-old Philadelphia man named Ronald Parks filed a federal lawsuit against EMTs and police whom he alleges handled him inappropriately during a February 1998 seizure. The Epilepsy Foundation of Southeastern Pennsylvania joined in the suit, which claimed EMTs and police don't receive proper training in how to handle seizure patients.

On July 26, 1999, the wife of a Passaic, N.J., man filed a wrongful death suit in federal court against police and EMTs eight months after her husband, who had epilepsy, had a confrontation with emergency services. Milagros Rivas claims that police choked, beat and cursed at her 44-year-old husband while she and other family members tried to explain he was having a seizure. He was pronounced dead at the hospital within hours of the call. The cause of death was listed as a heart attack, although the suit claims the cause of death was really asphyxia. According to police reports, Rivas was combative first with medical personnel and tried to bite a police officer. The State Department of Health has already fined EMS $1,500 for "incompetence or inability to provide adequate basic life support" to Rivas, noting that he was not properly restrained to a stretcher from which he fell down a flight of stairs.

In Los Angeles, a man died in 1998 after L.A. County Sheriff's deputies placed him in a total appendage restraint. A similar incident occurred in Scranton, Pa., in September 1999. Another man died in police custody in Silver City, N.M., in 1997 after being restrained by police and EMS personnel. Improper restraint use was implicated in each of these deaths.

Other cases involve inadequate restraints. In Stockbridge, Mass., recently, a 34-year-old woman died when she tumbled out the rear door of a moving ambulance. According to State Police, she worked her way out of a harness securing her to a stretcher during transport to a psychiatric facility.

In another case, a patient jumped from a moving Regional Emergency Medical Services ambulance in Genesee County, Mich., and sustained a serious head injury. The case was settled in November 2001 (Crouch v. Regional Emergency Medical Services, Circuit Court for the County of Genesee, No. 99-64580).

THE LAW

BALANCING PATIENT RIGHTS & SAFETY

Every patient encounter involves a delicate balance of patient's rights with the need for EMS to accomplish its legal duty once summoned. Under the U.S. Constitution, all patients have the right to determine what happens to their bodies; however, this right is not absolute.

A patient must have decision-making capacity: the ability to understand what's happening, know what medical treatment options exist and make an appropriate decision given their particular beliefs. Minors, the mentally ill, those patients under the influence of mind-altering substances or those who attempt suicide or are hypoxic or hypoglycemic may not have this decision-making ability.

EMS providers often find themselves in the difficult position of determining a patient's ability to make rational decisions, often with little or no information about the patient's history or usual demeanor. Subjecting a patient with decision-making capacity to physical or chemical restraints may leave you open to lawsuits for assault, battery and false imprisonment, as well as medical negligence.

UNLAWFUL SEIZURE & EXCESSIVE FORCE

In addition to the right to determine what happens to their bodies, patients have a Fourth Amendment right to be free of unreasonable seizures by the government. Thus, a patient tackled and restrained by public-sector EMS providers may have been seized under the law and may sue for civil rights violations, a growing trend in medical lawsuits. These lawsuits can involve extremely high damage awards if a jury feels the patient's constitutional rights were violated by government agencies.

Government agencies can be sued for deprivation of liberty without due process because liberty is a heavily protected right. Concerns about the use of excessive force pose issues for EMS as well as law enforcement if the method of restraint used is more than what's necessary for the patient's safety.

Patients who present as a danger to themselves or others, however, are the responsibility of the EMS system. The law considers these patients to be without decision-making capacity, so we must make decisions for them. Most states have statutes in their mental health codes that define the legal parameters for dealing with patients who pose a danger to themselves or others. However, we must treat and transport these patients without causing them further harm. Proper restraint and transport of these patients for further treatment whenever possible may prove lifesaving.

RESTRAINTS: WHAT'S APPROPRIATE FOR EMS?

ACEP supports the careful and appropriate use of patient restraints. According to its 1996 position paper,

[Figure 3 Photo © Craig Jackson] |

|

A 1993 study showed that only 50% of the EMS survey respondents reported having protocols for the management of violent patients. Only 25% of the respondents in the same study reported having any training for assessing violent situations. |

The Loma Linda study found that although 35% of the respondents said their service had a specific protocol for managing violent situations, only 28% had ever received formal training in the management of violent encounters.

|

Multiple restraint methods exist. Check your department's protocols for approved methods. [Figure 4 Photo Courtesy University of New Mexico School of Medicine] |

In collaboration with their medical directors and legal counsel, services must develop a protocol detailing the types of approved restraints and their use. The protocol must be flexible enough to allow EMS personnel to use their judgment in determining what's appropriate for individual patients and call for quality-assurance reviews of all instances in which a patient is restrained.

To defend against the legal challenges that frequently arise, the protocol must call for detailed documentation of the reasons for restraint application, the methods employed and the monitoring of restrained patients.

When an individual is handcuffed, hogtied and placed prone on the ground, demonstrable changes in physiology seem to occur. [Figure 5 Photo © Craig Jackson] |

|

The risks associated with restraining patients are not merely legal. Serious medical issues also exist. A syndrome known as agitated delirium, associated with cocaine and methamphetamine use, can cause sudden death. No correlation is apparent between drug concentration and level of impairment or prediction of likelihood of an agitated delirium death. However, effects of chronic abuse of these drugs can add additional risk factors for sudden death – sometimes involving patients restrained due to violent behavior toward law enforcement and/or EMS.

Cocaine and methamphetamine both increase heart rate and blood pressure, making the heart work harder. |

Preventing sudden death is the most important factor in management of agitated delirium. You can best accomplish this with a combination of physical and chemical restraint.

The best pharmacologic agents to use are benzodiazepines, such as lorazepam, midazolam and diazepam. These agents are preferable to butyrophenones, such as haloperidol and droperidol, because the butyrophenones lower the patient's seizure threshold; cause extrapyramidal reactions (sudden impairment of muscle tone); have anticholinergic toxicities, which may further increase body temperature; and, perhaps most importantly, can prolong the QTc interval, resulting in potentially fatal dysrhythmias. |

|

The chemical restraint for many services is a benzodiazepine, such as midazolam or diazepam. [Figure 6 Photo © Mark Ide] |

The dose required for adequate sedation varies widely and depends completely on the patient's response. Although the stopping point is somewhat arbitrary, drug administration should cease when sedation is adequate to control agitation and the level or significance of drug side effects remains tolerable. Some patients have required doses exceeding 100 mg of diazepam, so providers should prepare for advanced airway management and ventilatory assistance, including endotracheal intubation as necessary.

Another sign of agitated delirium may be hyperthermia. EMS providers may overlook a patient's sweating, believing it results solely from the chase or altercation with police. However, patients with agitated delirium often have body temperatures elevated to unacceptable levels. Sedate such patients to prevent the generation of additional heat due to the agitation and externally cool them (e.g., remove clothing, apply cool water wipes, etc.). Obtain the patient's core temperature rectally (on sedated patients) because oral and tympanic temperatures are notoriously inaccurate.

[Figure 7 Photo Courtesy University of New Mexico School of Medicine] |

|

MANAGING VIOLENT PATIENTS: THE NATIONAL PERSPECTIVE

EMS organizations across the country have very different views on what restraint methods are appropriate for EMS services. Jon Politis, director of Colonie (N.Y.) EMS, says, "We have no formal training or protocols for physical restraints; we call law enforcement."

Russ McCallion, EMS operations chief for the San Francisco Fire Department, says, "There's an increasing rate of assaults against paramedics in this city. We often have no backup. We use soft gauze restraints and handcuffs if the paramedic has been through police department-approved training. Our citizens are quick to complain about the use of excessive force."

PHYSICAL RESTRAINTS

There's no one right way for EMS to accomplish patient restraints; several acceptable methods exist. One method: Providers can use a spineboard with straps to restrain an agitated patient.

This fourpoint method is medically acceptable and appropriate for most patients. [Figure 8 Photo Courtesy University of New Mexico School of Medicine] |

|

Using soft gauze to secure patients to a stretcher is a time-tested restraint method. It's medically acceptable, inexpensive, readily available on most EMS units and likely the most appropriate method for most patients. A four-point system of restraining both wrists and both ankles to the stretcher will accomplish safe transport in many instances. Other methods may prove more appropriate for extremely agitated patients. |

Leather restraints, frequently used in hospitals but not often found on ambulances, can be somewhat cumbersome to apply. However, they can be a good, safe restraint method for crews familiar with their use.

Handcuffs are most familiar as a law-enforcement restraint, and most EMS agencies shy away from them. However, if properly trained in their use and keys are always readily available, EMS personnel can appropriately use handcuffs to restrain violent patients. Because they're a hard restraint, handcuffs carry more potential for injury. Monitor patients accordingly.

CHEMICAL RESTRAINTS

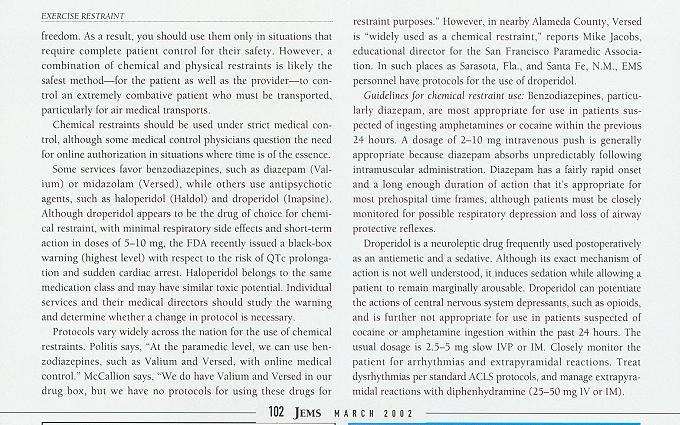

[The JEMS Web Site neglected to transcribe an entire section of this article

to their On-Line archive. The image below contains all of the missing text.]

Chemical restraints are highly restrictive in that they involve an invasive procedure that completely takes away the patient's

CONCLUSION

Recent lawsuits indicate the public and plaintiff's attorneys are looking closely at situations in which EMS applies patient restraints. Some lawsuits involve allegations of civil rights violations. Incidents of deaths during restraint have been reported in the literature secondary to patient restraints. Studies show that EMS personnel are frequently exposed to violence, but that education in the area of safe, legal restraint methods remains lacking. EMS training programs must pay more attention to this area of study.

Any restraint method should be approved by your service's medical director and legal counsel. EMS personnel should learn to recognize the indications for restraint and the proper method to apply restraints. Providers must closely monitor restrained patients and carefully document the restraint use. Quality-assurance reviews will ensure restraints are used appropriately.

REFERENCES

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

PUBLISHING AND REPRINT INFORMATION

"ADDITIONAL RESOURCES" from the above on this Web Site:

CHAS' REVIEW of "Exercise Restraint"

This review was finally written and posted on January 25, 2003.

Email Charly at: c-d-miller@neb.rr.com

Email Charly at: c-d-miller@neb.rr.com