NEW 2005 OPTION!:

A PDF File of “All Tied Up And No Place To Go”

All 3 parts in ONE place; thanx to Dustin Gammon, of Springfield, Missouri!

By Charly D. Miller, Paramedic;

EMS Author, Educator, & Consultant

In 1992, the University of Louisville, Kentucky, School of Medicine emergency department did a one-month study of patients requiring involuntary treatment (and restraint) orders.(1) They discovered that 49.5 percent of all the study patients (almost half) were brought to the emergency department by EMS services. The police transported 22.4 percent, family members delivered 21.7 percent, and 9 percent were self-referred (1.1 percent arrived by undocumented means).

Conclusion: the majority of patients requiring involuntary treatment and restraint are first encountered and managed solely by prehospital (EMS) care providers!

Unfortunately, specific techniques for safe and effective restraint application continue to receive inadequate coverage in all EMS training programs. Usually, when patient restraint issues do receive attention, EMS providers are merely directed to “have the police” accomplish restraint.

Anyone who’s worked in EMS for over a year knows that the police are not always available. MORE importantly, Law Enforcement restraint application does not meet the needs of medical restraint application. Indeed, Law Enforcement restraint often interferes with medical examination and care requirements. Thus, a mandate to “have the police” accomplish restraint is entirely inadequate to the needs of care providers and patients.

Patient Restraint should ONLY be employed to ensure Patient & Provider Safety, AND

to facilitate examination and emergency care of individuals with an altered level of consciousness.

“Combative” individuals are the least-often encountered reasons for employing patient restraint!

IN ORDER OF the MOST-FREQUENT LIKELIHOOD of NEED, here are the

Reasons For Patient Restraint:

In the United States, a citizen's right to refuse treatment, or transportation for treatment, is protected by law (common and statutory) and by his constitutional rights to privacy, due process, and freedom of religion.(1) A person has the right to come to what others might consider an “unreasonable” decision, as long as that person can make her/his decision in a “reasoned” manner – meaning the person is capable of reasoning, and is “competent” to make a decision.

COMPETENCE is defined as the capacity or ability to understand the nature and effects of one's acts or decisions.(2) And, for all practical purposes, a person is considered to be competent until proven otherwise.(3) Laws governing competence and the right to refuse medical treatment vary widely from state to state.(2, 6) Universally, however, the determination of competence generally depends upon four observable abilities.(3):

Then again, there also are situations in which the interests of the General Public

(“State Interests”) outweigh an individual's right to liberty:

MINORS are generally considered to be incapable of self-determination.(1) In the absence of a parent or legal guardian, and in the presence of a life- or health-threat, a minor may be treated against his will. The “freedom of religion” clause, whether it be the parent's or the minor's religion, is generally not allowed to interfere with a minor's treatment for a life- or health-threat.

Some states, however, have statutory provisions that allow certain minors the right of self-determination. “Mature minors” or “emancipated minors” may be defined, and therefore would have the same rights and responsibilities as an adult. For example, the state of Colorado defines a minor as any person under the age of eighteen.(4) But, Colorado also recognizes the right of consent for minors who are fifteen years old and older, living separate and apart from parent or legal guardian – with or without the parent/legal guardian's consent. Also, any married minor or minor parent has the right to consent within the state of Colorado.(4)

Some states, however, have statutory provisions that allow certain minors the right of self-determination. “Mature minors” or “emancipated minors” may be defined, and therefore would have the same rights and responsibilities as an adult. For example, the state of Colorado defines a minor as any person under the age of eighteen.(4) But, Colorado also recognizes the right of consent for minors who are fifteen years old and older, living separate and apart from parent or legal guardian – with or without the parent/legal guardian's consent. Also, any married minor or minor parent has the right to consent within the state of Colorado.(4)

CONSENT is defined as the voluntary agreement of a person possessing sufficient mental capacity to make an intelligent choice to do something (or not do something), in response to a proposition posed by another.(2) Consent is generally considered to be either expressed or implied.

Expressed consent is defined as positive, direct, unequivocal, voluntary verbal or physicalized agreement, and is a more absolute and binding degree of consent. Implied consent is defined as signs, facts, actions or inactions, which support the presumption of voluntary agreement. Thus, a patient who personally calls 9-1-1 could be considered as having implied a consent for evaluation and care.

Expressed consent is defined as positive, direct, unequivocal, voluntary verbal or physicalized agreement, and is a more absolute and binding degree of consent. Implied consent is defined as signs, facts, actions or inactions, which support the presumption of voluntary agreement. Thus, a patient who personally calls 9-1-1 could be considered as having implied a consent for evaluation and care.

Generally, the law implies patient consent during an emergency.(2)

The law has upheld that conditions which require immediate treatment for the protection of a person's life or health justify the implication of consent, if it is impossible to obtain express consent either from the patient or from one who is authorized to consent on his behalf. Thus, ANY unconscious patient may be treated under the auspices of implied consent. The courts assume that a competent, lucid adult would consent to treatment necessary to maintain health or life.

If the patient is clearly incompetent, she/he may be treated involuntarily. If circumstances are less clear, but there is legitimate professional doubt as to the competency of a patient refusing emergency care, it is best to err in favor of treatment. It is far better, legally, to be accused of “assault and battery” or “false imprisonment” secondary to involuntarily treating and transporting someone, than to later be accused of “negligence” for NOT having provided treatment!(2)

If the patient is clearly incompetent, she/he may be treated involuntarily. If circumstances are less clear, but there is legitimate professional doubt as to the competency of a patient refusing emergency care, it is best to err in favor of treatment. It is far better, legally, to be accused of “assault and battery” or “false imprisonment” secondary to involuntarily treating and transporting someone, than to later be accused of “negligence” for NOT having provided treatment!(2)

ASSAULT is defined as 1) an unlawful physical attack upon another; 2) an attempt or offer to do violence to another, with or without battery, as by holding a stone or club in a threatening manner.(5) Thus, “threat” – alone – can be considered an “assault.”

BATTERY is defined as an unlawful attack upon another person by beating, wounding, or even by touching in an offensive manner.(5) Checking a person's pulse without their permission may be considered “battery” by some patients. Members of some religions consider it extremely offensive to be touched by a person of the opposite sex; or for anyone to touch the head of a child. Thus, simply touching persons, without first obtaining permission to do so, may be considered “battery.”

FALSE IMPRISONMENT is defined as restraint without legal justification.(6) False imprisonment is considered a civil law and does not require violent abduction. Its equivalent in criminal law would be “kidnapping.” The mere threat of confinement, combined with only an apparent ability to accomplish confinement, and some limitation of movement (i.e.; a closed door), is sufficient to uphold a charge of false imprisonment. However, false imprisonment cannot be claimed if the patient consents to being confined.

When faced with the apparent need to involuntarily treat and restrain a patient,

FIRST consider the needs of the PATIENT.(7)

Would failure to restrain and/or treat the patient result in imminent harm to the patient or other specific persons? Most patients in an emergency setting are emotionally “upset.” Merely being “upset” does NOT support the use of restraints. There must be an indication of lack of competence, coupled with imminent health- or life-threat, before any patient can be treated involuntarily.(2)

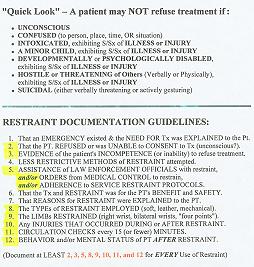

Thankfully, there are several patient characteristics/conditions that CLEARLY justify involuntary treatment and/or restraint. A patient may NOT refuse treatment if she/he is:

In most states, a person who exhibits a danger to her/himself or others (verbally or physically) may be taken into custody under an emergency mental health hold (MHH).(6) This hold is usually placed by a police officer or psychiatric medicine official. It is always wisest to have police present during incidents involving involuntary treatment and/or restraint.(7) (Both for purposes of legality and for sufficient assistance in the restraint of an individual.) Unfortunately, waiting for the police to arrive is not always an option (such as when the patient is in eminent life-threat, or when third parties are endangered and cannot be removed from the dangerous patient's vicinity).

Any form of restraint must be “INFORMED” restraint.(6) Even when the patient's lack of competence (confusion) will obviously prevent their ability to understand your explanation, you still must explain why you are restraining and treating the patient prior to doing it.

Occasionally, a patient will actually prefer to be restrained.(8) Restraint may provide them with a sense of safety or control. When you suspect this to be the case, OFFER restraints in a supportive manner, and solicit the patient's assistance with their application. If the patient cooperates with restraint, this cooperative action implies a consent to be restrained.

The DUTY of the prehospital health care (EMS) provider is the second consideration in providing restraint or involuntary treatment. Through personal commitment, professional oaths, and ethical medical principles, an EMS provider has a responsibility to provide the best possible care for every patient.(2) This care, and the way in which it is provided, is subject to measurement against national and local “professional standards of care.”

Without a Specific Written PROTOCOL for Patient Restraint,

Without a Specific Written PROTOCOL for Patient Restraint,

EMS providers who apply any kind of restraint are UNGUIDED and UNPROTECTED!

Every EMS service should have specific written guidelines for patient restraint that are approved by the service's administration, medical director, and legal counsel. Application of restraint for the purposes of patient care is then supported by these service protocols – but only as long as the protocols are strictly adhered to and the restraint situation is adequately documented.(9)

Every EMS service should have specific written guidelines for patient restraint that are approved by the service's administration, medical director, and legal counsel. Application of restraint for the purposes of patient care is then supported by these service protocols – but only as long as the protocols are strictly adhered to and the restraint situation is adequately documented.(9)

NEGLIGENCE: When duties or standards of care are not met, a legal action may arise based on the principles of negligence.(2) To succeed in a negligence action, the plaintiff (the suing party) must prove ALL of the following four elements against the defendant (the health care provider):

The EMS provider's responsibilities to individuals other than the patient – the “third parties” related to the incident is the third restraint or involuntary treatment consideration.(2)

It is a fundamental legal principle that all persons are required to use ordinary care not to injure others. When encountering a patient who manifests a danger to others, by verbal threats or threatening physical actions, the EMS provider may have a legal duty to control the patient, OR to safely evacuate the threatened parties, OR to at least notify appropriate authorities (police) to effect control of the threatening party and ensure the safety of third parties.

It is a fundamental legal principle that all persons are required to use ordinary care not to injure others. When encountering a patient who manifests a danger to others, by verbal threats or threatening physical actions, the EMS provider may have a legal duty to control the patient, OR to safely evacuate the threatened parties, OR to at least notify appropriate authorities (police) to effect control of the threatening party and ensure the safety of third parties.

In the state of Colorado, if a combative or violent patient injures another person, and an EMS provider was present prior to the injury, if the EMS provider is shown to have been capable of preventing that injury – but did not, the EMS provider may be held liable for the third party’s injuries.(2)

In the state of Colorado, if a combative or violent patient injures another person, and an EMS provider was present prior to the injury, if the EMS provider is shown to have been capable of preventing that injury – but did not, the EMS provider may be held liable for the third party’s injuries.(2)

Once The Decision To Restrain And Involuntarily Treat A Patient Is Made,

Other Legal Implications Come Into Play.

The LEAST RESTRICTIVE MEANS OF CONTROL must be employed.(1)

Technically (and legally), verbal communication is the “least restrictive” means of control. Therefore, verbal cues must be documented as having failed to control the patient prior to the use of physical force.(8)

Verbal de-escalation can be successful only when the provider:

Unfortunately, these verbal de-escalation techniques are entirely unlikely to be successful with patients who are intoxicated, patients who are confused, or patients who have an altered level of consciousness (for any reason).(10)

PHYSICAL CONTROL should occur ONLY after failure of verbal control:

Physical control is the “next step,” but also must be performed using the least restrictive means of restraint necessary to meet the patient's immediate and emergent needs. Arbitrary use of “4 point” restraints (chest and lower limb restraints, restraint of both wrists and both ankles – the most-restrictive form of physical restraint) may constitute a breach of this rule. If it can be established that the patient's care could have been safely accomplished while using the lesser-restriction of only 1- or 2- point restraint (chest and lower limb restraints, restraint of one or both wrists – but no ankles), the arbitrary use of 4-point restraint may result in successful litigation.

Thus, restraint application should be a gradual process. Begin with basic body restraints (chest and lower limb restraints) and a single-limb restraint. Progress to include restraint of additional limbs ONLY when the patient demonstrates a need for such increased amounts of restriction.

Thus, restraint application should be a gradual process. Begin with basic body restraints (chest and lower limb restraints) and a single-limb restraint. Progress to include restraint of additional limbs ONLY when the patient demonstrates a need for such increased amounts of restriction.

Obviously, there are exceptions to this “gradual process” rule. Later, we will discuss specific patients and situations, and how much restraint they can reasonably be expected to require in order to successfully assess them and provide appropriate care for them.

Obviously, there are exceptions to this “gradual process” rule. Later, we will discuss specific patients and situations, and how much restraint they can reasonably be expected to require in order to successfully assess them and provide appropriate care for them.

Only “REASONABLE FORCE” may be used when applying physical control.

A general rule for a “reasonable” amount of force is: the use of force equal to, or minimally greater than, the amount of force being exerted by the resisting patient.(7)

“REASONABLE FORCE” is also required to be a SAFE amount of Force.

Prior to applying ANY physical force, enough providers must be present to insure patient and provider safety during the restraint process. Optimally, a minimum of five people should be available to physically control a patient during restraint application: one for each limb and major joint, one to direct actions and apply the restraints.(2, 11)

Never hesitate to wait – at a safe distance – for adequate assistance, if you don’t have enough people to ensure the safety of patient and providers during restraint application. Remove all persons from the patient’s vicinity (at least ensuring protection of others), and wait for adequate assistance. Injuries that occur as a result of excessive force, or due to insufficient provision of safety during restraint, or from improperly applied restraints, present a serious legal liability, and any providers who participate in such inappropriate restraint may be successfully sued.(11)

Never hesitate to wait – at a safe distance – for adequate assistance, if you don’t have enough people to ensure the safety of patient and providers during restraint application. Remove all persons from the patient’s vicinity (at least ensuring protection of others), and wait for adequate assistance. Injuries that occur as a result of excessive force, or due to insufficient provision of safety during restraint, or from improperly applied restraints, present a serious legal liability, and any providers who participate in such inappropriate restraint may be successfully sued.(11)

DOCUMENTATION OF RESTRAINTS:

Improper or inadequate documentation of restraint will damn you in a court of law. If what you “recall” about patient-care delivery and management (actions that occurred many months – even years – before) does not fully correspond with what you documented, your credibility is discounted.(9)

When you have restrained a patient, you “SHOULD” document all of the following:

Certainly, not every restraint situation requires such extensive documentation. I routinely document only those points numbered 2, 3, 5, 8, 9, 10, 11, and 12. However, we are all familiar with the litigious nature of today's society. Whenever you have restrained someone who strikes you as having a litigious nature, or when the bystanders or family members strike you as having a litigious nature, the more of these points that you document, the more protected you will be by your documentation.

|

reference card similar to this one, so you have a handy on-scene or post-scene restraint reference, GO TO THE QUICK LOOK CARD PAGE! |

Email Charly at: c-d-miller@neb.rr.com

Email Charly at: c-d-miller@neb.rr.com